A Summer Like No Other, With Noone Left Behind

Include this article in your Skills Builder Journal. It could help you develop...

Writers’ Club member Jaden talks about full inclusivity this summer…

After two years of lockdowns, it’s safe to say that everyone is ready to embrace the freedom of a “return to normal” summer. Large crowds are permitted, meaning festivals and parties are in full force. 200,000 pairs of feet stomped the fields of Glastonbury and thousands of us marched together at Prides across the country, with flags and banners streaming down the streets of our major towns and cities.

Whilst some of us revel in the freedom of gigs and parties and parades, some of us are still experiencing the realities of quarantine. COVID-19 didn’t impact everyone in a universal way, the Government’s COVID-19 impact survey reported greater levels of loneliness in the disabled community, along with other impacts on mental health. The narrative that “COVID-19 only seriously affects the already vulnerable” spreads the harmful message that disabled people’s lives are less valued, and the emotional consequences of this are impossible to define with data.

One of the hardest parts of the pandemic was spending long periods of time alone in our homes. During the lockdowns we adapted by meeting up online with our friends and family, maintaining a sense of community within our individual homes. Online events became a lifeline in the face of constant isolation. For some, it was a huge relief to return to the shops, cafés, and cinemas where our busy lives once played out. For others, the switch to online socialising offered a chance to engage in a life that was once inaccessible. Venues without wheelchair access, sign language interpreters, or legible signage are unwelcome spaces for those who need them. Online events removed the fear of not being able to get through the door, let alone safely attend the event. Despite this, there is no excuse for organisers to use inaccessible venues and justify this with an online substitute.

Is a truly accessible event one that provides both physical and digital access, the provision of masks, the option for people to stay at a safe distance from crowds or to stay at home altogether? Could this mean disabled artists and creators won’t have to choose between their careers and their safety?

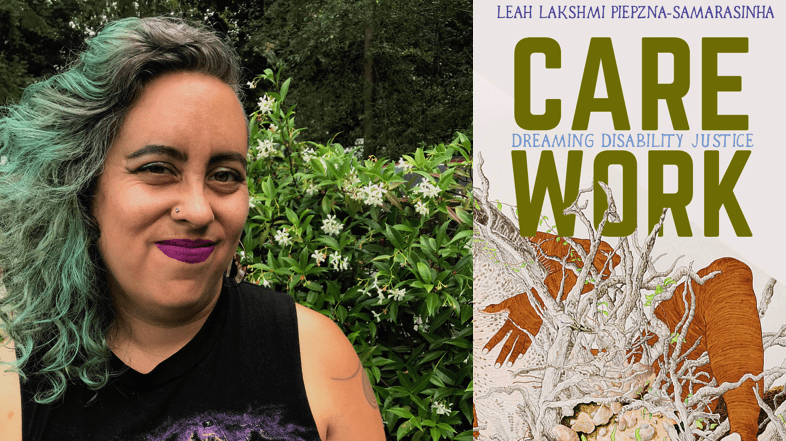

It shouldn’t go unnoticed that chronically ill and disabled people have been using the internet to build communities for years. In her book Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice, Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarashina outlines how the disabled community has created unique forms of accessibility through decades of activism.

This incredible excerpt displays how mutual support is played out in Leah’s small community of disabled activists when they attend a conference:

“We didn’t just survive the conference- we made a powerful community. Committed to leaving no one behind, we rolled through the conference in a big, slow group of wheelchair users, cane users and slow moving people. Instead of the classic able-bodied conference experience most of us were used to, where able-bodied people walk at their able-bodied rate and didn’t notice we were two blocks behind, or nowhere, we walked as slow as the slowest person and refused to abandon each other.”

I love the idea of defining allyship as moving “as slow as the slowest person.” The inner bookseller in me is begging everyone to read Leah’s book, it’s full of beautiful language that both humanises and empowers the collective work of disabled activists!

In 2010, a Facebook group called Sick and Disabled Queers formed a Care Network across the USA. Members of the group showed up for each other by providing both physical and emotional support. The group became a country wide mutual-aid project, highlighting the power of collective action and the leadership skills of disabled people of colour.

In 2014, Alice Wong founded Disability Visibility, an online cultural community of disabled creators. The goal of the project was to provide a free public archive of art and cultural history centring the disabled experience. During the pandemic many writers and activists shared their experiences. This is another great resource for anyone looking to expand their understanding of disability activism.

So what do truly accessible events actually look like?

An accessible event will accommodate the full spectrum of disabilities, understanding that some disabilities are invisible, physical, or sensory. Some involve sensitivity to lights, sounds and crowds. Events that are not just accessible but inclusive, actively engage with the needs of everyone.

In an interview with Munroe Bergdorf for the The Way We Are podcast, Fashion critic and activist Sinéad Burke explains that inclusivity is “everybody having the space to feel safe.” As a little person, Sinéad’s experience of inclusivity is defined by arriving at a space and “finding a footstool available or going to an accessible bathroom and tampons are also in that bathroom the way they’re in the women’s bathroom.” Here Sinéad highlights the importance of understanding intersectional needs, that disabled people also exist in the world with racial and gendered identities that need to be considered.

Sinéad goes on to explain the structural issues surrounding inclusivity, and how it is “not just an individual responsibility, but is about the systems that are around us that require justice and change (in order) to be designed better for everyone.”

Sinéad highlights the importance of big structural changes in the way we approach public life. Perhaps this is the summer we collectively start to challenge the ways our world has become increasingly unwelcome for people with disabilities, rejecting a return to normal and pursuing a return to inclusivity.

Ask yourself what it means to move at the pace of the slowest person among our friends and families, in our schools and workplaces and in the wider community and start from there…